The lost chimpanzees of Tenerife

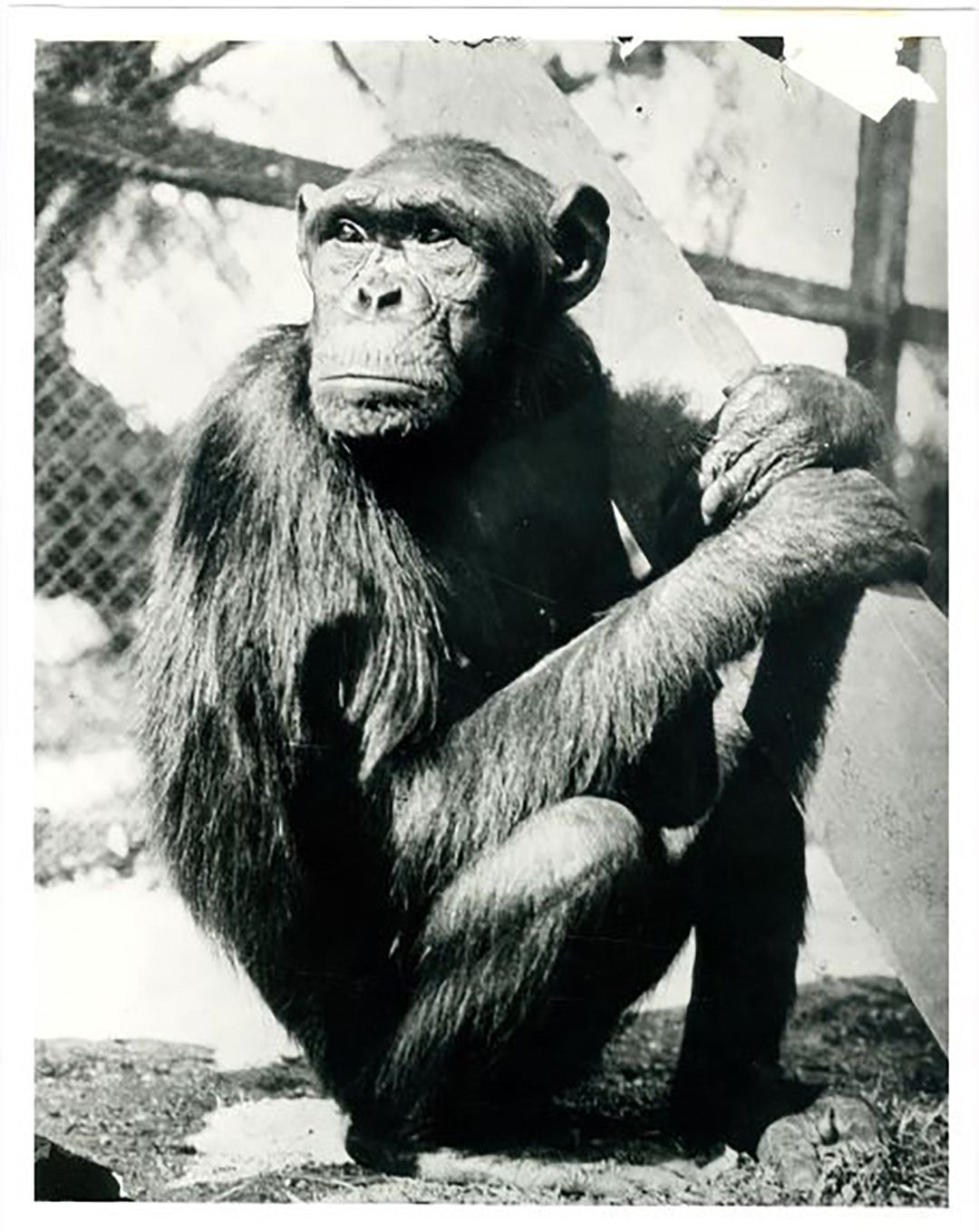

The chimpanzees in seminal early 20th century psychology research showing their problem-solving capabilities are being honoured in a research project capturing their full and sometimes tragic life stories.

Sleuthing by Associate Professor Javier Virués-Ortega has already led to the rediscovery of remains from five of the chimpanzees in German psychologist Wolfgang Köhler’s research, left forgotten in a Berlin museum’s storage for 100 years.

“These are the lost chimpanzees of Tenerife,” says Virués-Ortega, a behavioural psychologist at Waipapa Taumata Rau, University of Auckland. “Köhler’s breakthrough research featured in psychology text-books everywhere, but the animals were forgotten.”

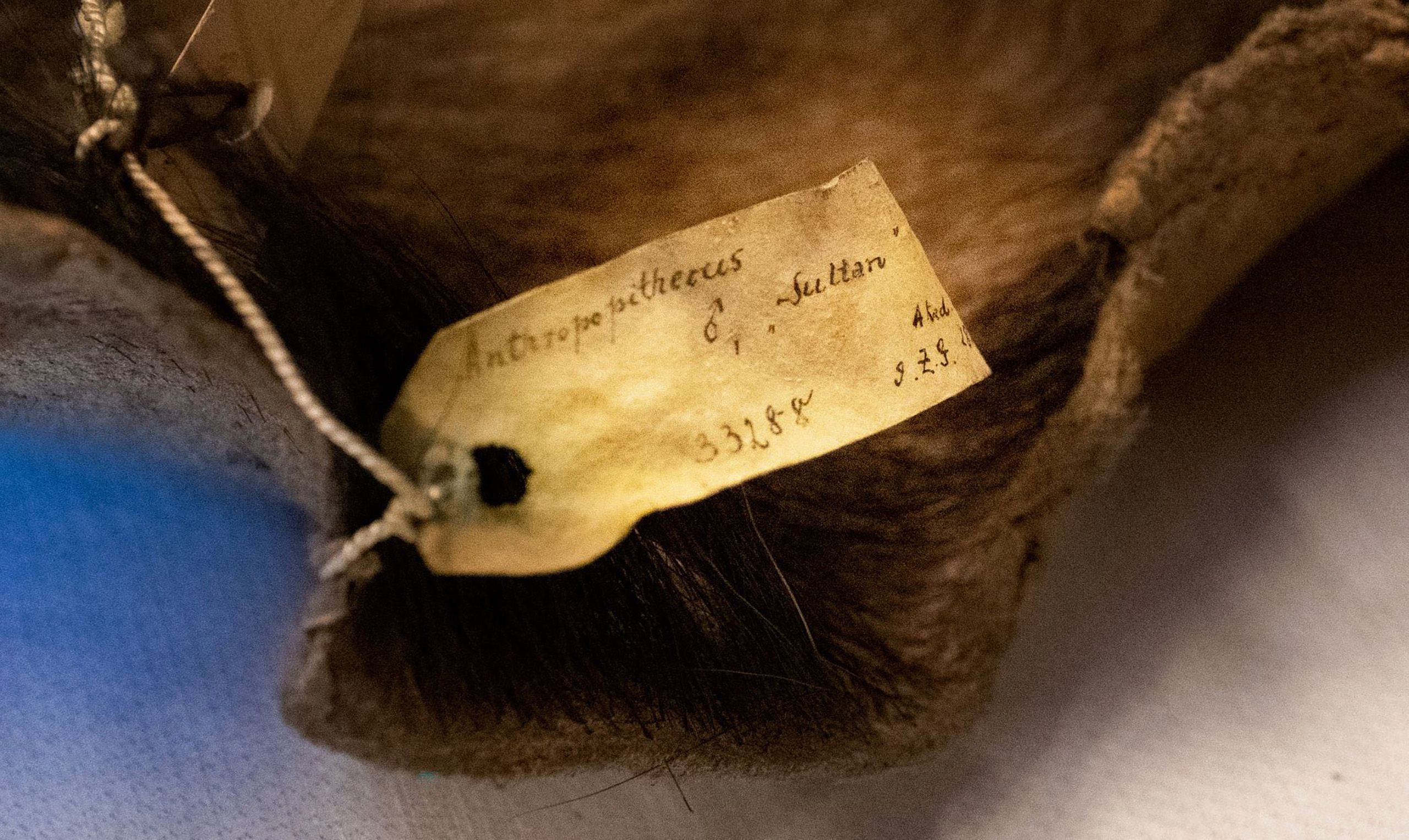

A museum tag on the remains

of chimpanzee Sultan.

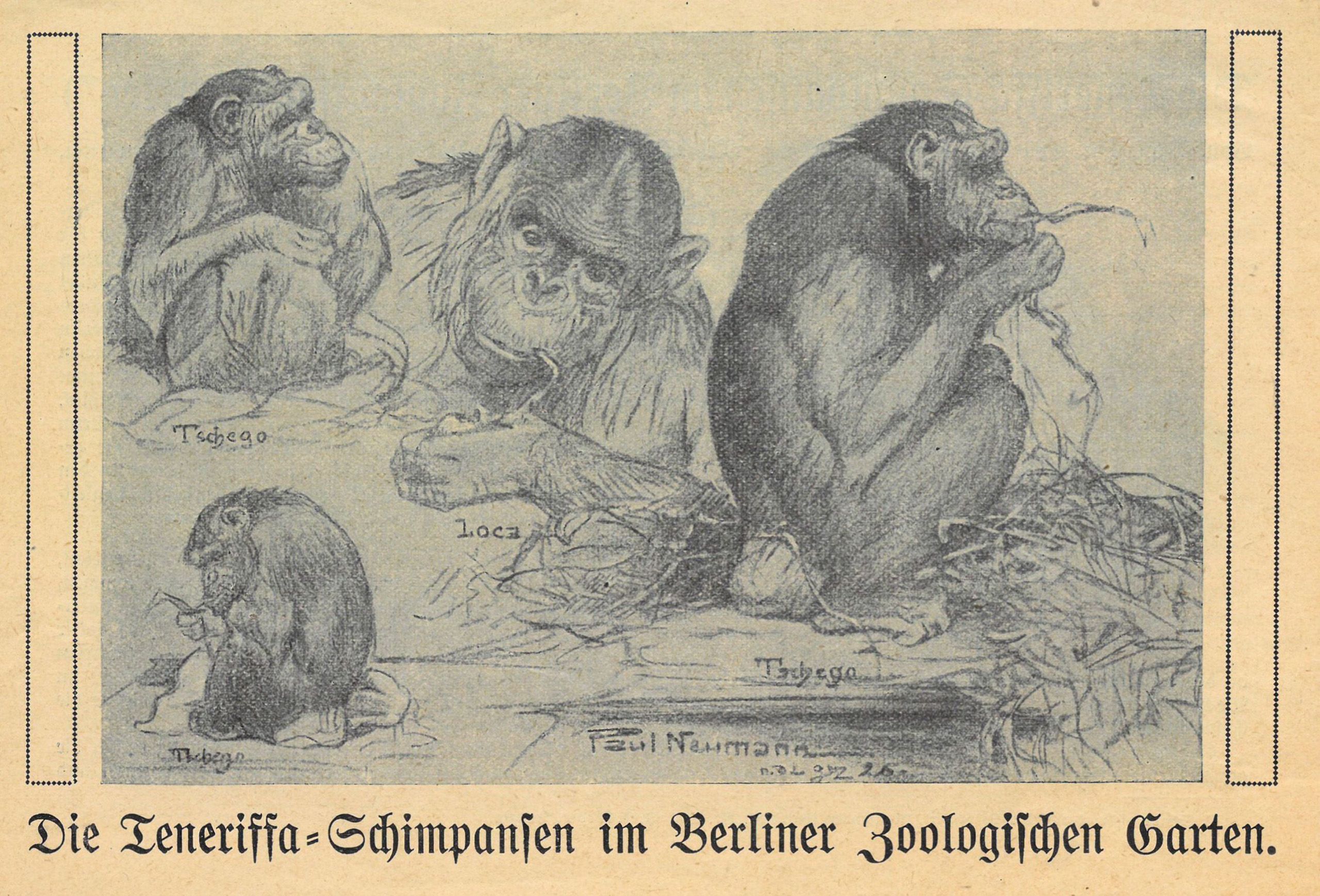

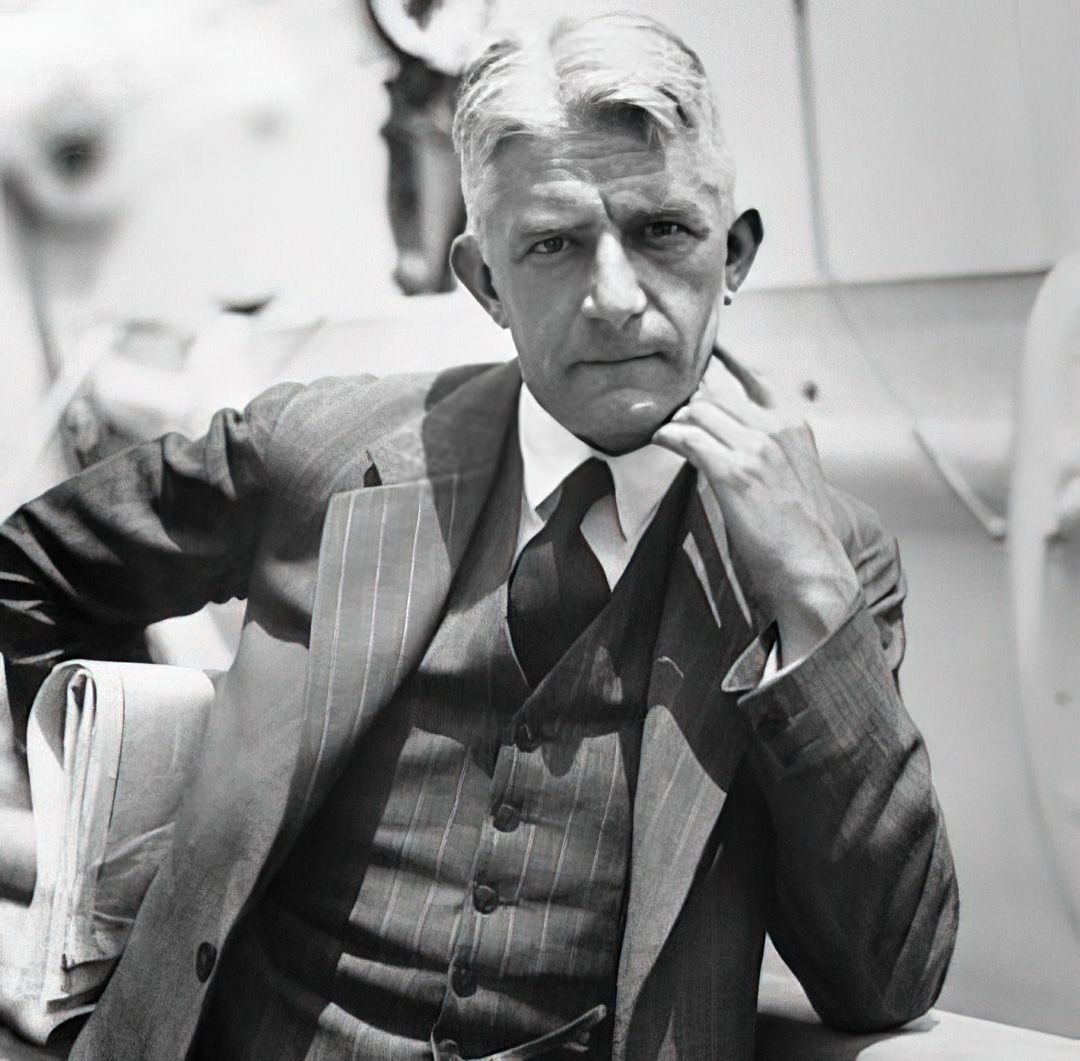

Dr Virués-Ortega is directing a documentary and writing papers about the chimpanzees, whose problem-solving abilities were studied at a research station on the island of Tenerife in Spain’s Canary Islands off West Africa from 1914 to 1920.

“With this work, we will attempt to dignify the memory of these individuals that redefined the very nature of human and animal intelligence; they played a critical role in the emerging study of intelligence, comparative psychology, and primatology,” he says.

After the publication of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution in the mid-19th century, scientists wanted to discover whether complex behavioural repertoires could be identified in our closest evolutionary relatives, the great apes.

In one of the most famous episodes during Köhler’s research, a chimpanzee named Sultan realised that putting two hollow reeds together enabled him to reach bananas outside of his cage. This modest feat meant that tool building was not the sole province of humans.

Köhler’s 1925 book The Mentality of Apes proposed that chimpanzees were capable of creative on-the-spot problem solving (what Köhler called “insight”). “This notion had a tremendous impact on comparative psychology over the next century and fuelled much research,” says Virués-Ortega. “Köhler provided proof that some intelligent and complex problem-solving behaviours are recognisable in our closest relatives and are not unique to humans.”

Köhler's close observations of the animals were foundational for primatologist Dame Jane Goodall’s studies of chimpanzees in the wild in the 1960s. Scientist and science communicator Carl Sagan also cited Köhler’s work in his book on the evolution of human intelligence, The Dragons of Eden.

However, researching the chimpanzees’ entire lives reveals “untold suffering,” Virués-Ortega says. “They were captured from the wild in Cameroon as juveniles, mostly aged from two to three, which means that almost certainly the mothers were shot dead to acquire the babies.”

After the research station closed in 1920, six surviving chimpanzees were shipped by steamer to Europe and sold to the Berlin Zoological Gardens, where research continued, but the animals were sometimes treated as comical attractions.

Studying historical documents, Virués-Ortega and zoo historian Dr Clemens Maier-Wolthausen traced remains of five of the six chimpanzees to the Museum für Naturkunde (Natural History Museum) Berlin, where catalogues had recorded the animals’ names, but not their significance.

The remains include one complete skeleton (Tschego), one skull (Rana-Loca), and five full-body skins (Sultan, Tschego, Rana-Loca, Chica and Grande). There is also a stillborn foetus (Tschego's) preserved in alcohol. On Tenerife, Köhler’s treatment of the chimpanzees was humane by the standards of the time.

“Kohler made some pioneering contributions to the welfare of captive chimpanzees in terms of medical care, quarantining, ample and communal playgrounds and sleeping quarters, and non-punishment-based interaction with humans,” he says. “But at the zoo, the animals had a difficult time. The starch-based diet didn’t suit them, their habitats had no heating, which was especially cruel in winter, and they dwelled in empty environments with little to do.”

All died at least 20 years ahead of the typical chimpanzee life expectancy, with Sultan succumbing last, in 1923. Virués-Ortega is from Cadiz in Spain, has personal ties to the Canary Islands, and visited the derelict Tenerife research station during the Covid-19 pandemic. He hopes that bringing renewed attention to Köhler’s work and the chimpanzees could lead to the station being preserved.

In a draft paper, Virués-Ortega says his research is a “modest homage” to the animals. His collaborators include comparative psychology expert Dr Alex Taylor, of the University of Auckland, anthropological archaeologist David García Gonzalez, of the Universidad de Granada, Spain, and zoo historian Dr Maier-Wolthausen.

Dr. Virues-Ortega and Dr. Marques Bonet from Universitat Pompeu Fabra (Catalonia, Spain) plan to extract and analyse genetic samples of the Tenerife troop. Their goal is to verify the geographical origins and pinpoint the precise African regions where the chimpanzees took their first steps, to unveil a crucial aspect of zoo and wildlife history.

Research into the behaviour and cognition of chimpanzees continues today in places such as the Wolfgang Köhler Primate Research Centre in Leipzig, Germany. However, chimpanzees have also been used for biomedical research, a controversial practice that some countries have banned or severely restricted. In 1999, New Zealand was the first country to institute a ban on invasive research using great apes.