The Disruptor

How frustration led to the third most cited paper of the century

Psychologist Professor Virginia Braun is a scholar of gender, sexuality and health. Her research questions the cultural drivers shaping gender, and in particular women and how those influences affect everything from what women do with their body hair to the rise of genital cosmetic surgery and the ‘designer vagina.’

“I see my role as a critical scholar as questioning accepted norms and challenging embedded expectations, particularly of women and the constant gendered messages women are bombarded with, such as they must look and act in a certain way,” she said in an interview when awarded the 2021 Marsden Medal for outstanding service to science.

“One of my roles is to disrupt those stories, through academic research and also through the media. In doing that, I aim to raise questions about what we understand as normal, and ideal and what we think is not, and how those can limit people’s lives and well-being.”

She has published more than 160 publications, including more than 85 peer-reviewed journal articles and some 45 books and chapters in research texts. Her work has influence. After all, half the world has a vulva. But she acknowledges the select circle for her scholarship. “Critical psychology in gender and sexuality is a very specific approach to psychology. We move in small communities of scholarship. It’s not like you’re expecting world domination in any way, shape or form.”

But one paper has done exactly that. In 2006 Braun and her long-time collaborator Victoria Clarke, published their paper Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. They did not write it with any ambition of academic dominance, but from the duo’s dissatisfaction with muddled and inconsistent use of a method they knew held transformative potential.

Nearly two decades later, that paper has become one of the most cited research works of the 21st century, ranking third according to a 2025 Nature analysis with citation counts ranging from 100,327 to over 230,000 across five major databases. Braun says, “We knew it was well-cited, but had no idea of the scope and scale of the Nature analysis.”

A single paper changed the trajectory of their careers. Braun and Clarke are regularly invited to speak as respected experts at major international conferences. They have been commissioned to write text books on thematic analysis, that in turn have been translated into multiple languages. On her bookshelf is one of the latest translations, in Polish.

The paper has become one of the most cited research works of the 21st century, ranking third according to a 2025 Nature analysis

Braun’s influence stems primarily from her development and articulation of reflexive thematic analysis (TA), a qualitative method designed to identify and analyse patterns of meaning (or "themes") across data sets such as interviews, focus groups, or text. What sets their version of TA apart is its flexibility and its rigorous demand for theoretical transparency and researcher reflexivity.

“The approach is about themes,” Braun explains, “and for us, at the broad level a theme refers to a pattern of meaning. But we were always imagining themes and patterns of meaning related to a core experience or interpretation.”

The origin story of the landmark TA paper is revealing. Braun and Clarke began their academic lives under the intense methodological scrutiny of Loughborough University’s Social Sciences Department, a hub for critical psychology and qualitative innovation. As doctoral students and later as early-career lecturers, they grew frustrated by how "thematic analysis" was referenced without clarity or rigour.

“We seriously thought we were writing a paper that was like getting a whole lot of stuff off our chest,” Braun recalls. “We literally sat there in the house I was staying in for about a week, and we had all our books. We paced around, and one of us wrote, and one of us talked, and we just basically talked through it all and put it together as a paper.” They expected it to be “a little thing,” Braun says. “I thought maybe 20 people would read it.”

Instead, it became a foundational text for qualitative researchers across disciplines. Braun and Clarke’s thematic analysis has exploded in popularity for one simple reason: it is immensely useful. TA offers a systematic yet flexible framework for analysing qualitative data without being tethered to a single philosophical paradigm.

This has made it attractive across disciplines—psychology, education, nursing, media studies, public health, and more. A scan finds TA used in an influential paper analysing tweets on Covid-19, another examining New Zealand’s poor sexual health statistics, and a further questioning assumptions about water drinking behaviour.

Their 2006 paper provided a six-phase guide to conducting thematic analysis, now standard in qualitative methodology texts. But beyond these steps, what Braun and Clarke really championed was researcher reflexivity—an understanding that analysis is never neutral or purely data-driven.

“We seriously thought we were writing a paper that was like getting a whole lot of stuff off our chest,”

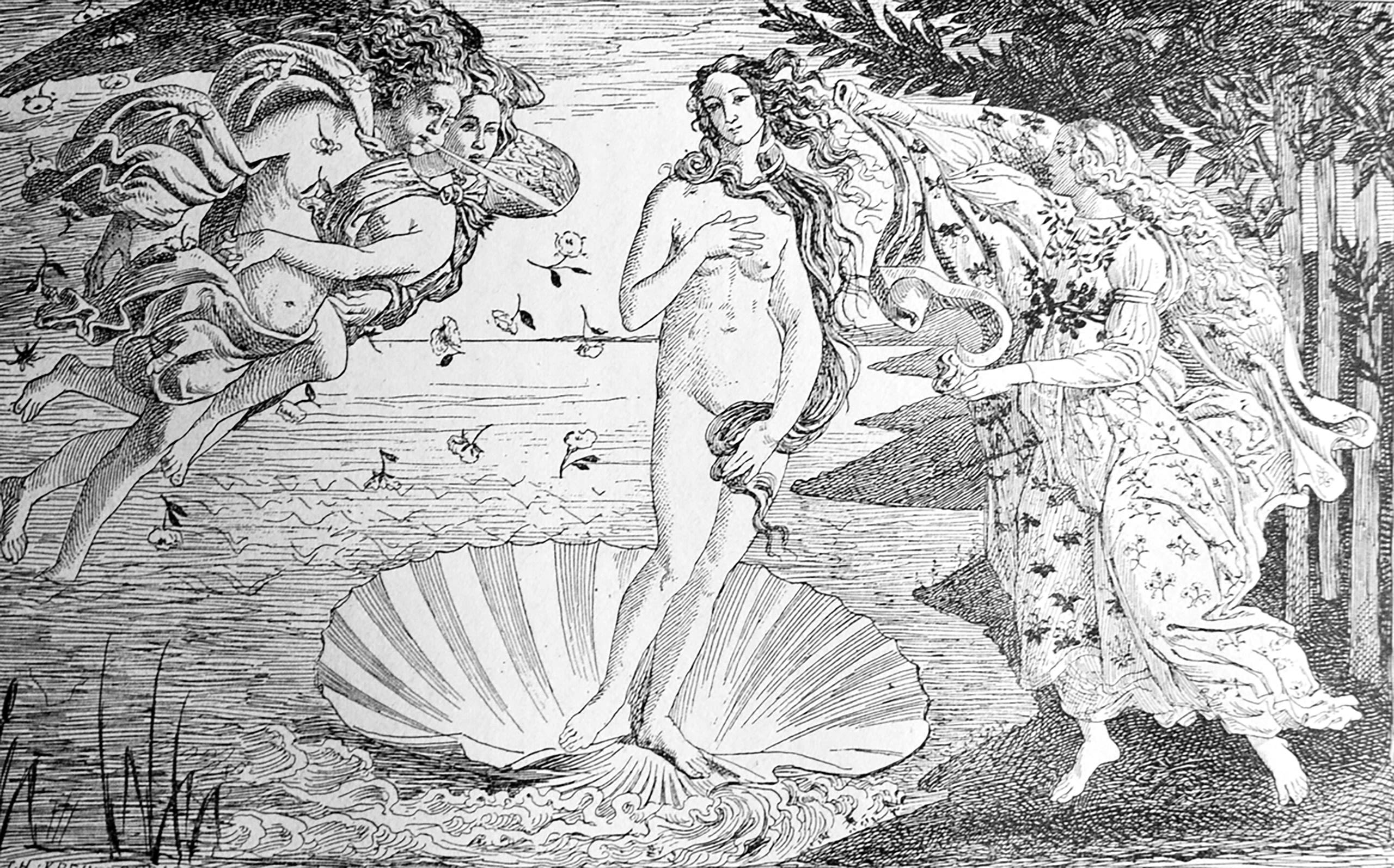

Braun dismisses the idea that themes just “emerge” from the data as “the Venus on the half shell” fallacy, an analogy from the paper. “A theme can’t emerge,” she says. “It’s the product of your analytic work. So, it’s not like it just bubbles up. It’s not pre-formed.”

That quote alone captures the deeper philosophical implications of TA: meaning is co-constructed by researchers in dialogue with data—not passively awaiting discovery like a fossil in the dirt.

“We were always imagining themes and patterns of meaning related to a core idea or meaning, an idea that united people's descriptions or their experiences. So, if you’re doing research on chronic illness a theme might be something like ‘feeling worthless’.”

Thematic analysis’s success has not come without complication. Braun acknowledges that the very popularity of the method has led to misuses and misunderstandings. “Anecdotally,” she says, “we have heard people saying they've been told that they have to cite it in their methodologies. And I'm like, well, if you haven't used it, why would you cite it?”

One of the most common misuses, she explains, is turning themes into mere categories. “So, you know, a theme is described as ‘visiting the doctor.’ That’s not what we intended.”

Braun and Clarke have collaborated on further papers analysing how others use their method. “We've actually done three or four analyses of uses of it as a methodological approach,” Braun explains. This review process has helped them refine their own thinking: “It’s been really useful, to ask what actually do we mean? What actually is this approach about?” They have even published “10 types of misuse” as a teaching tool.

TA is an approach, a tool for researchers, that Braun has frequently used in her own research, related to sociocultural representations of health.

This work includes research on female genital cosmetic surgery, vulvas, and cultural representations of health, risk and gendered obligations. It’s deeply informed by critical psychology, which she distils as how the ‘outside’ gets ‘inside.’

“We live with so many cultural narratives that say, ‘This is a good idea. You can do this. You can be this and if you do you will be better or more desirable. That’s what I look at with my research.” She weighs up the power imbalances between social classes and groups and how they affect physical and mental well-being.

TA’s flexibility allows it to “provide a tool for that kind of analysis,” Braun says, noting that it “is compatible with the kind of critical theories” she and Clarke work with.

Nor would she say that the paper is the final word on TA. Braun emphasises that it is a “theoretically flexible” approach. But she cautions against the temptation to use this flexibility as an excuse for methodological sloppiness. “Sometimes people think the method is atheoretical,” she says. This speaks to one of Braun’s key concerns: that researchers treat TA not as a plug-and-play technique, but as a conceptually grounded practice.

“You have to think: Are you treating language neutrally? Are you imagining a singular truth? Or are you imagining a complex, situated world?” That question, she believes, is at the heart of all good qualitative research. The most rewarding part of all this is seeing how others have taken up the method. “It's the gift that keeps giving.”

Will AI transform thematic analysis as it already has done in STEM research? She doubts that. “There’s already a lot of nonsense out there. Why? Because an AI can’t be the subjective interpreter reflecting on thematic analysis.”

At heart TA is a thought-based interrogation of the meaning of data. “I don’t know how you can get that without engaging with the data yourself.” Let’s say she is firmly “Team human.”

She and collaborator Victoria Clarke’s insistence on clarity, reflexivity, and honesty has empowered researchers around the world to explore the complexity of human experience with rigour and sensitivity to context.

In a research landscape dominated by quantitative metrics, AI-driven analytics, and scientific positivism, where only ‘facts’ produced through controlled and objective methods are the preferred basis of knowledge, Braun’s work is a counterbalance—a reminder that interpretation is not a flaw in the system but a feature of how we make meaning from the apparently random.

As she and Clarke write: “Themes don’t reside in the data. They reside in our heads—from our thinking about our data and creating links as we understand them.”