Ruby's legacy

Finding answers to a rare and terrible disease

In early 2019, Ruby Hill gave her final media interview. The 23-year-old had gastroparesis, a disease where the electrical contractions that cause food to go through the digestive system don’t work properly.

Four years earlier, Ruby had been a fit and healthy 19-year-old, training to be a pilot at Auckland’s Ardmore airport. But developing gastroparesis meant her body couldn’t absorb the nutrients it needed. She couldn’t keep food down and slowly wasted away; she died in April 2019. But not before setting up a challenge to find some way of helping people with chronic gut conditions like hers.

Her aim was that in the future people wouldn’t have to suffer what she had gone through. “If it was more researched and understood, like cancer, we would have more help,” she told NZME’s Michael Cunningham a month before her death.

It wasn’t just the physical symptoms – though they were terrible. It was the way she was treated, including by medical people.

As Ruby slowly starved to death she was told, ‘It could be worse, you could have cancer’. She was told she looked great, because she was skinny. She was told she ‘just needed to put on a couple of kilograms’ and she’d be fine. Some people refused to believe she wasn’t anorexic.

“It’s pretty disheartening,” she said at the time. “My goal is to help others. To make sure no one else goes through this.”

“It’s pretty disheartening. My goal is to help others. To make sure no one else goes through this.”

After Ruby’s death, her mum Jo Hill took up the challenge. In 2021, she set up a charitable trust, Ruby’s Voice, to increase awareness of gastroparesis and to raise money for its diagnosis and treatment.

Now a donation from the trust is helping fund a smart young New Zealand gastrointestinal researcher to travel to the US, where he will spend a year at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

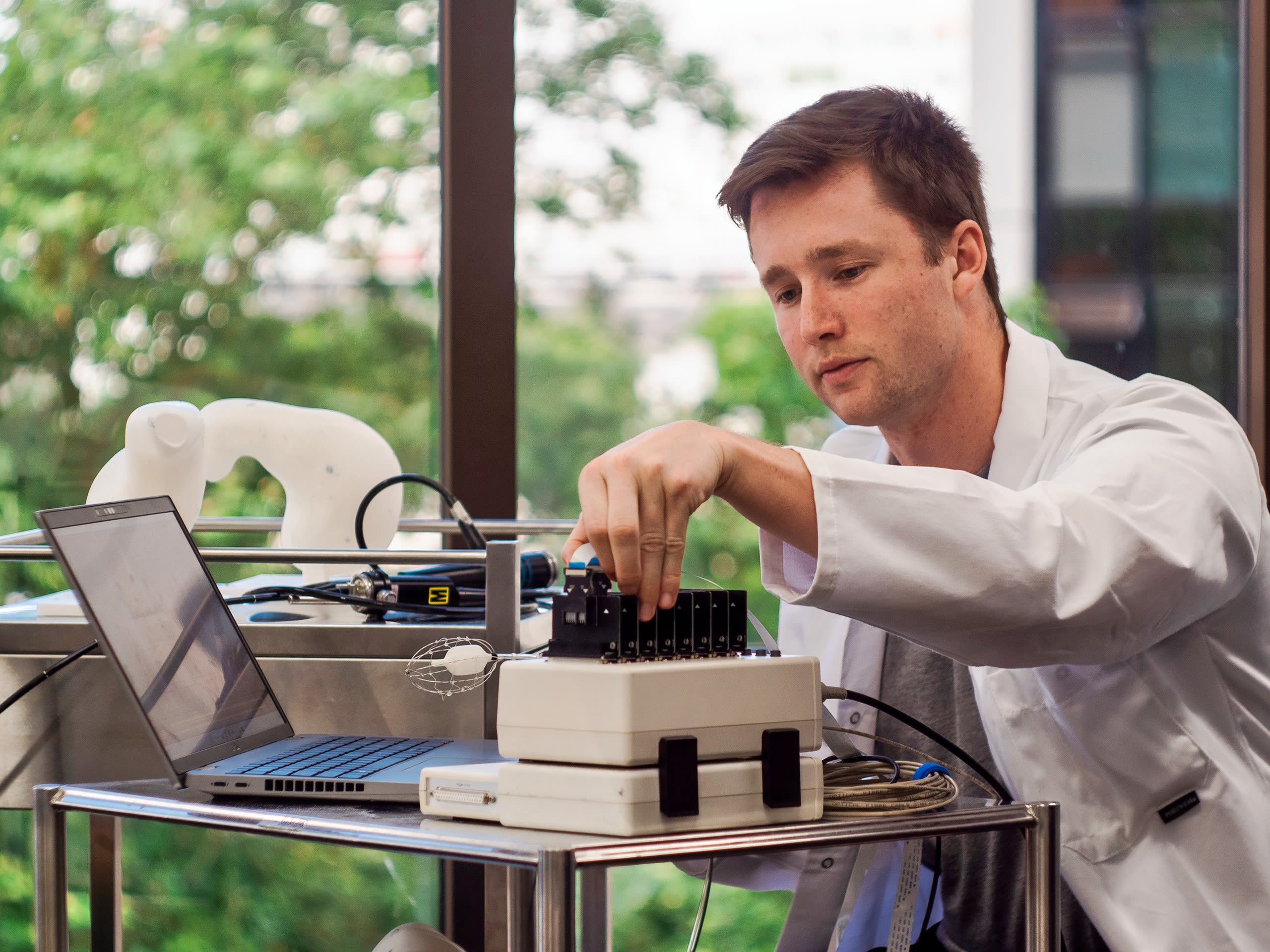

Peter Tremain is 27 – just a few months younger than Ruby would have been if she had lived. Tremain is a PhD student at the Auckland Bioengineering Institute (ABI) and is developing a probe that can be sent into the gut via someone’s mouth in order to measure electrical pulses. Think of it as a sort of internal electrocardiogram (ECG) for the gastrointestinal system.

Over the last few years, ABI researchers led by Senior Research Fellow Dr Tim Angeli-Gordon have discovered that (like in the heart) electrical signals going awry can cause big problems. In the gut that often means pain, nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea - symptoms that are often very difficult to diagnose or treat. As in Ruby’s case, they can cause death.

The problem is that electrical signals in the gut are weaker and so harder to detect than those in the heart. In addition, the exact location of any abnormalities is harder to pinpoint.

Tremain hopes his endoscopic device will change that. Imagine a deflatable Christmas bauble on the end of a tube. Where the outside of the bauble would be, is a skeleton made up of 64 electrodes, and once the device is inflated inside someone’s body, the electrodes send back data on the pattern of electricity in the stomach.

This enables doctors to work out whether that pattern is normal or not, thereby helping diagnosis and, hopefully, treatment. But the device is still at the development stage, which is where the Massachusetts Institute of Technology comes in.

“The problem we are trying to solve is deeply technical, and to achieve the best result, we need to draw upon all expertise available to us,” Tremain says. “The Traverso lab at MIT is arguably one of the best gastrointestinal (GI) device development laboratories in the world. Combining their knowledge with our world-leading experience in GI electrophysiology puts us in the best position possible to successfully bring our device to clinic.”

Gastroparesis is a relatively rare condition – a recent study determined around 0.8 percent of Australians may have the disease, equating to something less than 35,000 New Zealand adults.

But the potential impact of Tremain’s research could be far wider, he says. “The electrical abnormalities we target with our device work are applicable to a wider group of diseases called functional gastrointestinal disorders. These diseases have less severe symptoms than gastroparesis but still contribute to a lousy quality of life for many people.”

Functional dyspepsia, for example, is estimated to affect approximately 10-15 percent of the population globally, and gastroesophageal reflux disease affects up to 30 percent.

“So globally we are talking hundreds of millions or billions of people that could be helped through electrically-informed intervention, such as our work. In New Zealand that number will be in the hundreds of thousands to millions of people.”

Prototypes of the device. Image: University of Auckland.

Prototypes of the device. Image: University of Auckland.

So globally we are talking hundreds of millions or billions of people that could be helped through electrically-informed intervention, such as our work.

Jo Hill says the Ruby’s Voice trust is aiming to fund a research scholarship each year and is looking for donors in New Zealand and overseas. “It’s hard to get funding for students looking at gastrointestinal problems. Our trustees are really motivated to see things move forward.”